INTRODUCTION

Someone wisely said ‘if we take care in the beginning, the end will take care of itself’. This is true for the creation of both the protocol and the Case Report Form (CRF), which illustrates it, at the beginning of the clinical trial. If we take care in getting these two ‘right’ the remainder of the process, up to and including the Final Study Report, will take care of itself. Whatever medium is used for the CRF, paper, electronic or combina- tions of both, the CRF is only as good as the protocol. As a translation/ illustration of the protocol the CRF can never be better than the protocol or compensate for its inadequacies or oversights. Ultimately, the Final Study Report, which is the product of sophisticated computer programsand a statistical analysis, is only as good as the data collected in the CRF. The whole process from defining the data to be collected, collecting, checking, analysing and presenting it, is resource intensive, utilising soph- isticated technology and employing highly skilled professionals. Unex- pected delays can occur at any of these stages, which is costly. The process does not need the additional cost burdens and delays due to poor data quality or loss of data. Minimising these are within our control at the start with the protocol and CRF design.

FUNCTION OF THE CRF

The CRF is the tool we use to collect pre-defined data from a Subject in a clinical trial. The ICH Guidelines for Good Clinical Practice define the CRF as: A printed, optical or electronic document designed to record all of the pro-

tocol required information to be reported to the Sponsor on each trial Subject

Although considerable advances have been made in the study and produc- tion of electronic CRFs, the majority of trial data are collected on paper CRFs and the current review focuses on these, where the CRF refers to thetotal collection of pages for each Subject.

CLINICAL RESEARCH TRAINING CLICK ON LINK---------->>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>

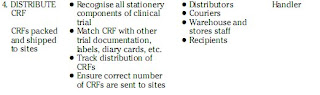

THE LIFE HISTORY OF THE CRF The CRF must be robust in content and material. The Life History Table,Table 3.1, illustrates the uses made of the CRF, and by whom, and the emphasis of use which impacts on the design. The Users can be categor- ised as individuals concerned with the data collected on the forms—Form Fillers and Readers, and those concerned with pages or whole CRFs— Handlers. Each User has created a process through which the CRF will pass. Ig- nore any User at your peril and delays will result. It takes less resource to incorporate their needs, within reason, in the design stage, than to amend the CRF during printing, or after distribution, or to expect Users to muddle through producing possible errors and/or delays

STAGE 1: PROTOCOL

As the precursor to the CRF, review of the protocol before it is final provides the designer with an overview of the clinical trial, and the oppor-tunity to assess its impact on the CRF design. Personal experience has shown that holding discussions focused on the CRF during the writing of the protocol produces a better final version and fewer protocol amendments.

Phases

The protocol defines the objectives of the study. Broadly speaking, these are concerned with safety and efficacy; the degree of emphasis for each is dependent on the phase of the clinical trial programme. Reviewing the protocol from this angle indicates the size of the task and where to focus energies for the design of the CRF. In general, early phase studies collect data over a short period of time,such as a large number of safety measurements and intense monitoring of the drug’s behaviour for a population selected by tightly defined exclu- sions, at a single site. By Phase III the sheer numbers of Subjects, studied for a longer period of time, using subjective questionnaires/opinions, more specific safety, efficacy and population details at many centres, add to the complexity of the CRF Time and Event Schedule The best review of the protocol is achieved by constructing a Schedule of Events against Time from the protocol text. The benefits of the exercise are:

(i) To highlight the Reviewer’s interpretation of the protocol which may differ from the Author’s.

(ii) To check for omissions/discrepancies of the proposed study events.

(iii) To highlight potential logistic problems for the CRF if numerous sources provide data for each Subject.

(iv) To generate a list of specific questions based on the following checklist:

● What data need to be collected if a Subject does not meet entry criteria?

● What standard data collection modules can be used? need modi-fying? are missing?

● What existing forms can be used?

● What new forms are needed?

● How is dosing/compliance being measured?

● What population-specific data are needed?

● Which data are needed for safety monitoring? efficacy?

● What happens if the Subject does not complete the study at any time point after enrolment?

STAGE 2: CRF DESIGN

Introduction

The CRF is a very specialised form. More forms are generated as our life becomes increasingly computer dependent. All forms collect data, but the use of the data varies, for example, applications, purchases and so on, which in turn influences the look of the form. Forms are composed of structured questions by someone else, demanding answers from us in a way that is foreign to our thinking and constraining to our freedom of expression of information. We are apathetic, possibly because we cannot interact with a form to, for example, clarify a meaning, request more space, provide an answer which has not been anticipated, or request a clean page if we make a mistake. Small wonder that for most, completing a form is a daunting task, and complex CRFs get a cool reception. Over the past 30 years or so, students of typography, ergonomics and occupational psychology have examined in depth the use of written lan-guage, presentation and various media in an attempt to measure the factors that facilitate reading, comprehension and action—known as Human Fac-tors. If these are understood, then we can incorporate those that motivate the Form Filler to provide better quality data into the structure of the CRF.The application of the findings to Clinical Trial forms was reviewed byWright and Haybittle when they proposed three aspects for

consideration1:

1. CONTENT—do you need to collect it?

2. PRESENTATION—are you asking the question correctly?

3. METHODOLOGY—what design alternatives are available to avoid/

minimise problems that Users have with the forms?

CONTENT—Do you need to collect it?

The protocol identifies the data to be collected during the trial to achieve the study objectives and meet regulatory requirements.

1. Date, phase and identification of the trial.

2. Identification of the Subject.

3. Age, sex, height, weight and ethnic group of the Subject.

4. Particular characteristics of the Subject (smoking, dietary, preg-nancy, previous treatment etc.).

5. Diagnosis, indication for which the product is administered in ac-cordance with the protocol.

6. Adherence to inclusion/exclusion criteria.

7. Duration of disease, time to last breakout, etc.

8. Dose, dosage schedule, administration of medical product, com-pliance record.

9. Duration of treatment.

10. Duration of observational period.

11. Concomitant use of other medicines and non-medicinalinterventions/therapy

12. Dietary regimens.

13. Recording of efficacy parameters met, date and time.

14. Recording Adverse Events, type, duration, intensity consequence and measures taken.

15. Reasons for withdrawal, breaking code.

Some study designs will legitimately omit a few of the above, for example,dietary regimens, breaking code, but the majority will be included.

The Mock-up CRF

General information that accompanies the mock-up will state:

● How the CRF will be finished?

1. Drilling? Crimping? Pads?

2. Folder? Ring binder? Covers?

● Numbers of CRFs required and when?

● Assembly instructions, order of pages

● Size, type, weight, colour, numbers, matt/shiny, thickness, etc. of all

materials

● Position and orientation of print on materials

● Materials?

1. Paper

2. Inks

3. Card

4. Tab dividers

5. Front sheets

6. Acetates or laminates

7. Attachment, insert stationery—wallets, folders, envelopes

8. Labels

9. Business reply cards?

Mark pages that require different materials, special printing, folding or binding on the mock-up.